Anti-war films are so rarely seen from the perspectives of the citizens of occupied or warring territories. We are shown soldiers fighting and dying and killing, because it is more exciting and dramatic. The issue therein is that for violence to be exciting, to be seen as ‘action,’ the audience must want one side to beat the other; they must be rooting for a victor. And while in many wars, sides can be taken, and one party is clearly more evil than the other, ultimately violence has no heroes. So, Ingmar Bergman shows us the lives of a couple which are upended by war.

While a lesser writer might have began the movie with a portrayal of a perfect romance, two wealthy and happy people deeply in love, and then shown them be tortured and blown to smithereens, Bergman once again takes a less traditionally dramatic approach – we see two real, imperfect people with insecurities and issues and arguments. When war kicks down their door, we do not see it as a destruction of paradise, but as a destruction of normalcy. During the first act we follow Jan and Eva as they squabble, despair and rejoice. Their conversations are usual; they are usual. They have money troubles, but they splurge on a bottle of wine to share. They disagree, yes, but they apologize and move on when things get too personal. They discuss their future together. And then, its existence is called into question.

Bergman understands that the element of relatability is vital to tragedy, and he uses it to great effect here. Moreover, the possibility of these characters dying is more saddening than if Mr. and Ms. Right died – Jan and Eva have progress to make, in their relationship and as individuals. They have room to grow, and they want to. Especially since this is a Bergman film, we expect character arcs, and for the first half hour, it seems as though we’ll get them. Then, before any change can occur, Jan and Eva are thrust from their stable, albeit flawed lives into a hellscape. Rather than being shot or captured or killed, as they might be under another filmmaker, they are set adrift, put in danger and left to stew. Their story is not one of an adventure or an escape or even of violence, really; they are trapped, waiting for death. The death, were it to come, would seem almost a relief, a release from uncertainty. As a result, the arcs-to-be are splintered and we instead must witness how their new circumstances affect their relationship. The cracks in their bond, which with time would have been closed and healed, are by the reality by which they are now confronted opened further, until empty space is all that is left.

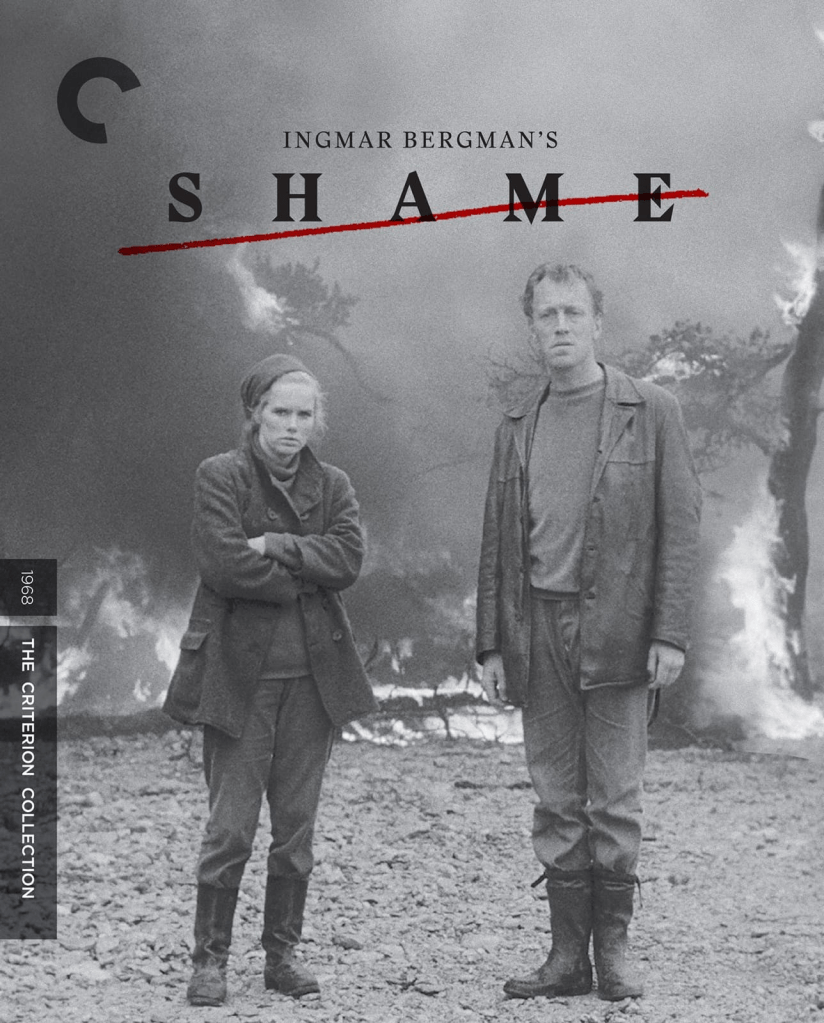

Liv Ullman and Max von Sydow, frequent Bergman collaborators, play the couple with a complete comprehension of their writer’s intention. The way they work both together and at odds to play out their mutual unraveling at the hands of exterior forces is something almost musical, like an expansive duet. They ebb and flow and clash on screen, all while performing in perfect harmony. Their sorrow and bitterness at the world is taken out on one another, and received with such a convincing mesh of resentment and understanding, all hidden behind the expected solemn collaboration of partners undergoing trying times. The subtle chemistry between the two actors is the film’s greatest strength, one that it wields deftly; Bergman is forever a master of showing off his performers.

Shame is a film so wrought with uncertainty, so unsure to its core, that it often becomes somewhat inscrutable as to what it’s trying to say about its protagonists. Though it’s lamentations on war are quite direct, even trite, it’s unorthodox manner of handling characters is somewhat ethically nihilistic. Watching a movie, a viewer instinctually judges the actions and reactions of all the characters, searching for some goodness and some badness, some right and some wrong. With this film, Bergman seems to attempt to be objective, both in depicting the horrors of war and in creating his wayward characters. As the plot progresses, we experience a certain decomposition of civility, watching the formalities fall away and seeing people revert to animalistic instincts when put under immense physical and emotion strain. The script does not call for much commentary – on the contrary, it makes a point of not making a point, of standing alone as a narrative, as if to say, ‘do not assess, do not evaluate, simply watch.’ As if to remind us what savagery the best, most average of us are capable of when we absolutely need to be. So, posits Bergman, let’s not make each other need to be so capable.