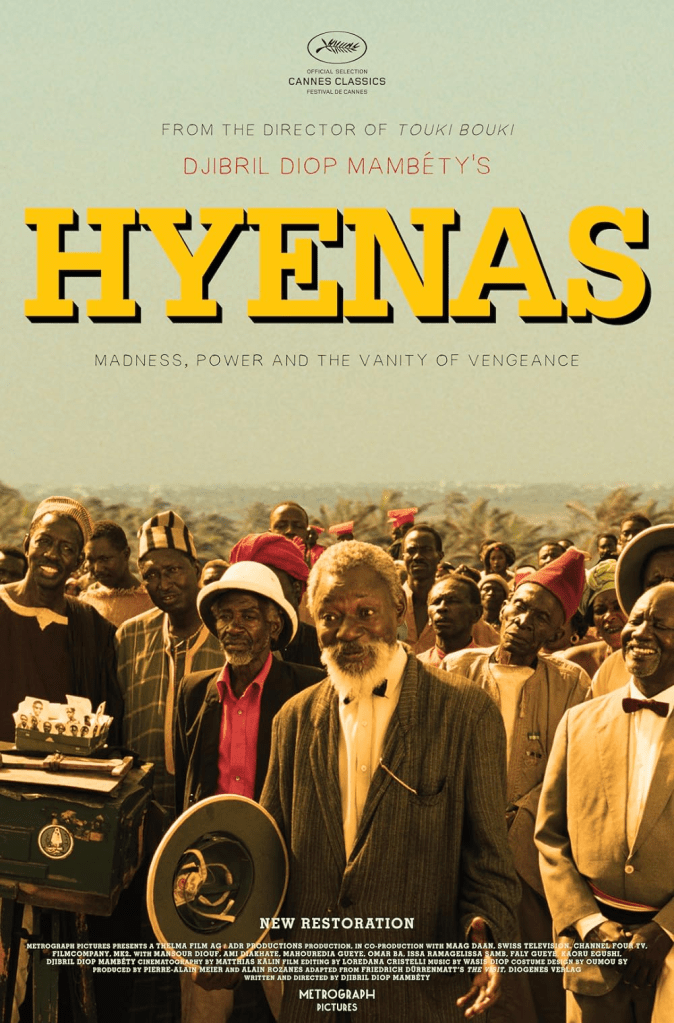

Hyenas is a scathing critique of both capitalism and the patriarchal system it represents, the twist being that the two are separated and pitted against one another. The film’s two protagonists, Dramaan Drameh and Linguère Ramatou, are each representative of one of these two evils. Dramaan, representing the patriarchy, is a popular elderly grocer in his hometown of Colobane, in line to be the next mayor. As a young man, he impregnated and abandoned Linguère, leaving the child to die and her to become a prostitute. Now a very wealthy woman representative of capitalism, Linguère returns to Colobane with the promise of an exorbitant sum of money for the impoverished town, on the condition that Dramaan is executed.

The film is set up as an exemplum, with simple characters and a clear-cut conflict, leaving room for moralistic commentary. As the sides, both of which are to some extent in the wrong, define themselves, it seems as though the screenplay will compromise itself by choosing between the lesser of two evils. However, writer/director Djibril Diop Mambéty is able to masterfully weave through the plot without choosing a side; he takes an objective look at the fable-like narrative, and leaves it without a definite lesson. Dramaan certainly mistreated Linguère, but he is not directly responsible for much of her misfortune, at least no more than he is for her financial success. Linguère certainly has a right to damn him, but a death penalty seems a bit drastic, and to hold an entire town hostage by withholding funds they could use for food, shelter and education as a means to a vengeful end is nothing short of dystopian. Dramaan is supported vocally by his neighbors, who profess their solidarity and never once question his innocence. “We’re not in America, we don’t shoot people for nothing!” exclaims one townsman, eager to defend Dramaan even as he buys cigarettes he couldn’t afford the day before. In fact, nearly all of Dramaan’s customers are now buying expensive and extravagant items, not paying up front but requesting that the bill be put on their tabs. The mayor purchases fridges and television sets for the town, and everybody has brand new yellow shoes. When Dramaan seeks help from local authorities, from the mayor, from his peers, everybody tells him the same thing; it’s preposterous that they would kill him, they aren’t savages.

What wins out, prejudice or manufactured necessity? Thus asks the story, with the town’s trust and admiration for its male everyman at war with their basic rights and luxuries, which have been stripped away by rules made to benefit others. How Linguère acquired her riches is never explained, for good reason – she seems like some mystical being of splendor, of greater importance than the peasants around her. She is treated as royalty, as a goddess, with speeches given in her honor and dances performed for her enjoyment and even a throne for her to sit on. She is not viewed by the community as having a quality of character, but rather as a figure, not unlike a law or branch of government. To the community, they must betray their own to save themselves, as decreed under the almighty rule of the wealthy. The situation as it is presented to us is a bit more complex, though, because Dramaan is guilty, and Linguère does have a certain character, however obscure. In reality, the townspeople do not have to betray their own, but rather choose between the upholding of the established order, or the entrance of a new, possibly more destructive one. People take sides vehemently, some more publicity than others, but nonetheless fervently; they choose, proudly, between the two evils, seeing at least one as viable and just and apt. People rejoice as their chosen order rises, or despair as it falls.

Eventually, the irony overtakes the drama. How ridiculous it is that these are the only outcomes – essentially, death or bondage. How ridiculous that people decide, and debate, and hope for one over the other. Rather than question the choice itself, they squabble and pontificate. They see nobody to blame, only an inevitability. The excuses they make for themselves and for their situation are nothing short of comical in their shallowness, and they reflect a certain vapidity onto the townspeople; these are people who act first and create principles after. These are people who follow, who answer the questions they are asked with a yes or no. These are the stereotypes of society’s cannon fodder, the voters or poll results that become not individuals, but numbers. They are strikingly reminiscent of a herd of animals, doing whatever they can to survive through sheer luck, navigating a course drawn by a higher power. What outcome the town chooses is unimportant; most telling is that they choose.

You don’t wander the jungle with a ticket to the zoo. To partake in the lion’s feast…one has to be in the same league. Proper people are people who pay. And I pay. You’ll cover your hands with blood, or remain poor forever!

Linguère Ramatou