Yorgos Lanthimos’ new anthology film Kinds of Kindness is surprising; difficult to describe; and unique in how it must be analyzed. It has a modern sheen – the stories seem to take place is a near future, although I can’t place anything distinctly futuristic about them…it is simply that society has evolved strangely. The most fascinating aspects of the movie are all the vague similarities between the plots, and between actors’ respective parts in those plots (each story has the same cast playing different characters), and yet these connections are all so intangible and thematic. I adore Lanthimos’ ability to illustrate the human temperament and condition in such absurd terms, and that’s exactly what these connections serve to highlight: the relatable, relevant truths within the absurdity. The first segment was my personal favorite of the three – I don’t know why, but I always find myself enjoying the segments of anthologies less and less as they go. Corporate cog Jesse Plemmons follows extreme and personal instructions from his boss, until he fails one order and subsequently, desperately tries to repair the relationship. Meanwhile, his relationship with his wife suffers. With it’s cruelty, harsh power dynamics, and emphasis on betrayal, Lanthimos paints a nightmare of a job’s ultra-personal demands that feels prescient in a world of increasingly demanding employers and professional dehumanization. In the end, Plemmons’ cog miraculously salvages his relationship with his boss after multiple unambiguous rejections – his delusion, that the relationship was salvageable, is validated.

In the second segment, the dynamic between police officer Jesse Plemmons and the woman he believes to be an imposter of his wife is difficult to get a grasp on, but with his personal outbursts and constant, ever-subtle abuses of power, I think this Plemmons is Lanthimos’ vision of the bad-person-everyman, especially in relation to American culture and politics (the police stuff is really charged). The validation of his delusion in the end, at least through his perspective, by the miraculous arrival of his real wife while the supposed imposter bleeds out in the living room, is such a purposefully morbid bow to put on things – as if to look the audience (or whoever is being addressed: police, abusers, those neglecting love) in the face and ask, “Is this really a happy ending?” Yorgos thinks a happy ending would be a world run by dogs.

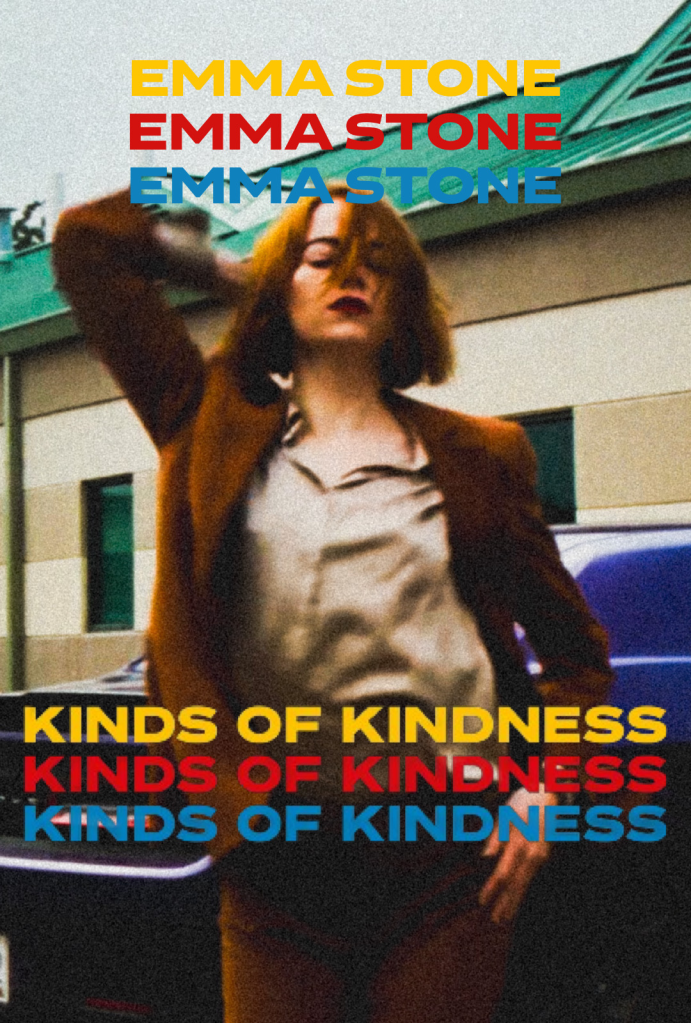

The third segment is the weakest, a mishmosh of cynical lampoons of domesticity, but the ending is the really meaningful part in relation to the other stories: our protagonist, Emma Stone, miraculously uncovers the supernatural element she has been searching for, validating her delusion, then gets herself into a car wreck, destroying the supernature just as everything was going her way. All three stories are generally about fragility and lack of control, each happy ending followed by catastrophe and each catastrophe followed by a happy ending. Lanthimos takes care to let us bathe in Stone’s happy ending before the crash, with that instantly-iconic frantic dancing wide shot – it’s another happy ending after all, every happy ending is followed by the unhappiness of life. There are ups and downs, but no real endings. The enigmatic RMF finds himself at the center of various strange and senseless situations throughout the film, few of them pleasant – in a mid-credit scene, he eats a sandwich simply. When a condiment falls onto his light shirt, he wipes it off without notice and returns to his meal. He doesn’t react to the food, really, but it looks good.