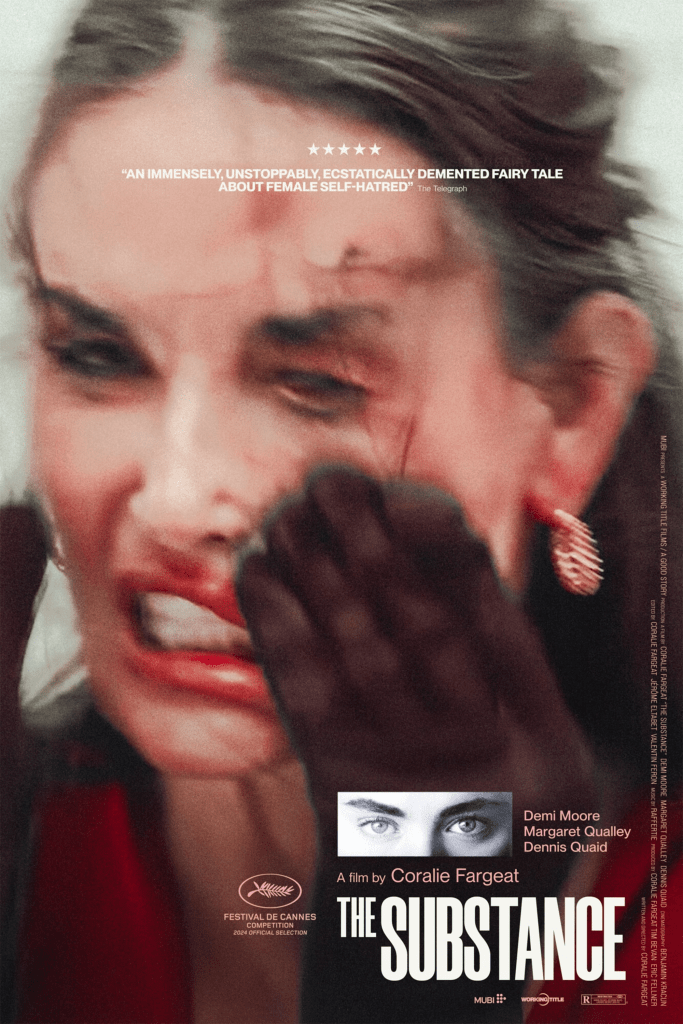

Unless Megalopolis shocks me, I’ve just seen the greatest movie of the year. There will be extensive overuse of parentheses in this review, because this phenomenal future classic has sent my mind reeling with thematic possibilities and left me high on the power of cinema and story alike – excuse me in advance if my writing seems scatter-brained, but I cannot fathom another way to unpack such an aggressively multifaceted film. Be warned.

Writer/director Coralie Fargeat’s greatest feat with her gruesome social satire The Substance, for me, is to have (I’m making a conscious effort not to say ‘was’, for reasons obvious to anyone who’s seen it) created an experience so simultaneously enthralling and discomforting. I suppose the same could be said of her dazzling debut feature Revenge, itself a satire reworking the rape-revenge subgenre’s sexual lens to incredible, reinventive effect, but there’s no comparing the discomforting side of the two; The Substance pulls no punches and offers minimal catharsis. It’s an almost impossibly disturbing endeavor – disturbing the status quo of the mind into a position of allyship – and one that ups its own ante at every turn. There were an uncountable slew of moments at which I was certain the credits would roll, only for things to get worse yet, but not such that the narrative overstays its welcome or mutates past recognition; it continues and exacerbates inevitably, because so do our insecurities, so does our torment, so do our insatiable demands for beauty both in ourselves and in the content we consume.

We follow – it may be more accurate to say we are – washed-up Oscar-winner and former sex symbol Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore in the knock-your-socks-off performance of her career), now the face of a fitness program out of the 1980s that has inexplicably survived this long, but cannot survive any longer, according to her sleazy executive boss (Dennis Quaid in, somehow, the performance of his career – though he always plays it delightfully camp, there’s a genuine understanding to his portrayal of a misogynist that displays his hitherto-hidden chops), now that she’s turned fifty. Out of the line of sight of a camera for the first time in decades, Elisabeth collapses in on herself and seems bound for isolation, alcoholism and depression, as is all too common with stars the industry assigns as faded, until she is introduced to a miracle cloning drug called only ‘The Substance’. Apparently, The Substance will create another version of herself, one more young and beautiful and “perfect”, whose body she will inhabit every other week. The One Rule? She cannot forget the two entities are both one and the same – herself. As you’ll expect if you’ve ever seen a sci-fi with One Rule, she cannot wrap her mind around this cardinal piece of information, and the two versions of herself are almost immediately waged in battle. What these two versions may represent in an allegorical sense is somewhat vague, but my take away (after only one viewing – this is a film with many layers that deserve many revisitations, so take my speculations with a grain of salt) is that there is a true self and another, false self constructed by the augmentations we make when we are presenting ourselves to others – that one is false and one is true does not stop each from having an equal stake in the psyche, and does not give either an edge in the conflict between the two. Though Elisabeth hesitates at first, the haste with which she soon injects this mystery Substance into her veins is less a conceit we have to buy into and more a striking comment on just how little she feels her life is worth outside of the spotlight. In fact, many moments I predict will be brushed off as unbelievable or far-fetched are not intended to be taken as realistic, but rather to be taken as points.

We are so forced into Elisabeth’s perspective, both through story and through constrictive direction that makes her point of view, and by extension her body, a suffocating prison, and though we maintain her narrative perspective when she shifts to her “perfect” body – which, in her first violation of the One Rule, she names Sue – we become visually at odds with her, looking at her rather than with her. We become the very gaze that obsesses and haunts her, and leads her to self-destruct. (Also of note is the palpable implication that Elisabeth, and to a much more obvious but less intriguing extent Sue, is complicit in the propagation of that gaze; during the one filming we see of Elisabeth’s aforementioned ‘80s-style workout show, she motivates the female viewer with descriptions of what she’ll look like in a bathing suit, and as any self-respecting gym rat will tell you, making your body look a certain way is never the reason you should be exercising.) Fargeat is able to seamlessly move between these modes of looking-with and looking-at, even as Elisabeth’s transitions become more and more arduous – this is another area which she practiced in Revenge, where we watch the protagonist through the eyes of ogling men and then watch them suffer through her avenging eyes, and perfects here. Revenge was a film that became a minor fixation for me when I first saw it three years ago, first for its unprecedented style even in the violently macabre and then upon rewatch and further visual inspection for the way it co-opts the male gaze to the aid of its feminist assertions of female agency (while men are watching, inactive save for their slobbering looks, watched women are acting, in both the doing and performing senses of the word). Many elements of Revenge make a welcome comeback in The Substance, and I hope they’ll be mainstays of her coming filmography (which I await with more excitement than any two-time feature director I can bring to mind at the moment): the overwhelming barrage of colors (here penetrated by scenes in suddenly sterilized environments, and helmed by cinematographer Benjamin Kracun, whose work alongside Emerald Fennell on filmic feminist gold standard of the decade Promising Young Woman was a major factor, perhaps the inciting factor, in my induction into the world of film), the extreme closeups of things we least want to see up close (Quaid stuffing his face with shrimp while delivering a terrible blow to our protagonist directly replicates a similarly nauseating sequence in Revenge), the subversions of rampant first-act cliches (presented with such conviction and cohesion the we never suspect they are being set up to be taken down), the bloodthirst behind (perhaps caused by inhabiting) beauty, and of course those glittering star-shaped earrings (now white rather than bright pink; this may simply be because the outfit worn with them in The Substance is already pink, but at the risk of reading too deeply, the change may also be a reflection of the differences between the reasons for their wearing; while Revenge’s Jennifer wears them as a means of self expression, here they are ostensibly given to Sue by yet another male member of the crew, leading me to consider something along the lines of the pressures of purity even in sexuality).

Although Fargeat has spoken against overly referential filmmaking, believing it to be detrimental to the audience’s experience by pulling them out of the movie they are watching – she calls these “second-degree moments,” and as a fellow fan of Kill Bill I know all too well what she means – The Substance certainly wears its influences on its sleeve. These influences are many, from gialli to classical horror to Cronenberg and Carrie, but only a select few (Carrie among them) reach the level of what I would consider homage. Even those are very subtle – Fargeat is careful to distance her film from, well, all others. It’s first and foremost unique, which is why I feel these influences stand out so much and are so fascinating to me. I’m sure there are countless I didn’t notice (I’m excited to rewatch The Substance after watching some movies I have yet to see but from which I suspect it takes inspiration due to their reputations and subject matters alone), but I still think it’s of use to consider three of those I did for their insights into Fargeat’s thematic and tonal intentions. I tackle them in no particular order.

Requiem for a Dream will surely be brought up in many post-movie conversations for The Substance’s dethroning of that film as containing the most revolting injection (or extraction) site, but what may be left out of said conversations is the similarities between the effects of those unwatchable moments of self-abuse by needle on the respective characters; both become permanently disfigured. And Leto’s character isn’t the only one from Requiem whose end mirrors the trials Elisabeth/Sue undergoes – all four Requiem protagonists, by the end of their film, have a striking amount in common with E/S. Consider Connelly’s Marion, who is repeatedly sexually debased in her escalating interactions with dealers and wealthy men offering money during her desperate search for another hit (the transactionality of these interactions is also mirrored by E/S’s interactions with men); Wayans’ Tyrone, worked to the bone with no end in sight and imprisoned; and most potently Burstyn’s Sara, an overeater (like Elisabeth, who gorges herself, apparently starving, upon returning to her body, but Sue markedly never experiences anything comparable – proving this detail speaks not merely to a symptom of the body change but to Sue’s eating habits, likely motivated, as with seemingly everything else, by body image) who becomes addicted to ‘diet’ pills given to her by her doctor as she tries to fit into a dress so that she’ll be presentable on the television show she wastes away in front of all day (again like Elisabeth, who finds herself trapped on the opposite end of the camera as before the change, comparing herself and being constantly reminded what her body used to be), and who ends up medically tortured and socially humiliated. These endings all represent recurring agonies plaguing E/S’s journey, but none match her own dismal end. Of the three homages, this to me seems the most obvious, and that may well be by design – it serves extremely well to highlight the more subtle addiction E/S is experiencing, of spotlight and attention and perception rather than literal substance (other than the obvious titular, of course, but that stands so removed from reality it cannot be taken as anything other than allegorical. The real compulsion is to fame, and it’s a compulsion forced on E/S by patriarchal pressures of performance, once again similar to pressures in the stories of both Marion and Sara).

Rather than conform, some homages of Fargeat’s contrast. Last year’s Barbie was such a cultural milestone that for its sociopolitics to be recognized and rebuffed by what is, I write cautiously, the next major feminist outing to play in theaters nationwide is inevitable. At the time of its release and since, I have seen little to no criticism of Barbie’s feminism by anyone who is a feminist or in any way understands the tenets of feminism; by which I mean, the loathsome assholes it mocks seemed to be the only people to take vocal issue with what it has to say. Yet there exists in Barbie’s subtleties some frankly sickening misuses, manipulations, and ignorances of its overstatedly-feminist themes. It was a movie so abrasive in its messaging that the slighter implications of its form of delivering those greater messages, which I found extremely crude, utterly flew under the cultural radar. I don’t want to be the one to do a Barbie takedown – I am not a woman, and I cannot speak to the experience of womanhood – but since The Substance’s references to the Barbie movie’s shortcomings are just as subtle as those largely unnoticed shortcoming themselves, I find it necessary to illustrate those references of Fargeat’s. (Please keep in mind as I continue that this remains speculation on my part, that Fargeat has not, to my knowledge, made any direct comments on Barbie or confirmed that The Substance in any way responds to it, and that, once again, I am a man who, to the extent of my perspective, hasn’t a fucking clue what he’s talking about. The remainder of this topic should be taken with a significantly lighter grain of salt than my speculations before and after.) First there is the insidious ‘bubble-gum feminism,’ as it is often called, in which Barbie engages; though this term has yet to secure a solid, consistent definition, suffice it to say that bubble-gum culture, beginning in the ‘90s and 2000s, represents a form of femininity based almost entirely on image and presentation, and thus inextricably tied to the male gaze and male standards which inevitably determine female appearance in a patriarchal society. Think Britney Spears and the trials she endured, and passed down to the women and girls of her audience who of course idolized and emulated, as her image was ruled by the visions of men (there’s a particularly harrowing passage of her recent autobiography, The Woman in Me, where she describes performing with a giant snake around her shoulders of which she was terrified – “I felt if I looked up and caught its eye, it would kill me” – the phallic a literal burden, a literal danger; I’m hard-pressed to think of any fictional scene with such appallingly relevant symbolism). The Barbies we look at in the film are dressed to impress, slathered in uniform makeup, and, with the exception of a few almost comically one-note token characters with little-to-no screen time, look from afar like a homogenous Mormon harem of skinny, hyperfeminine light-skinned women. The sole outlier, Kate McKinnon’s “weird Barbie,” is yet another such woman whose femininity is merely hidden beneath the use she has endured by children playing with her – and the moral of her involvement in the story boils down to, ‘we shouldn’t be so mean to the weird one even though she’s weird’. And by the film’s end, unrepented misogynists are allowed back into otherwise-utopian Barbieland because exclusion of the intolerant from an otherwise safe space is wrong (read sarcasm). Sue, with her male-manicured appearance and agreeable, nothing-(allowed-)behind-the-eyes demeanor, would fit right in alongside Margot Robbie’s and Emma Mackey’s Barbies (two actors whose talent and choice of roles I generally have great respect for). Sue presents herself thus (or rather, is presented thus) on television, to influence women and girls nationwide, to imprint the idea that this false self of augmented presentation is indeed a real, constant self to which those female viewers should aspire. What kind of a role model is a Sue or a Barbie, as superficially independent as they may be? Where, in Barbie, is the hideous monster hiding in the shadows who, by sheer contrast, makes beauty so stark? What of her? We know she must exist for Barbie to be Barbie, for Sue to be Sue. Fargeat offers an answer: she is on the other side of the camera, the other side of the television set, watching, being influenced, being compared, internalizing. She is the girl at home, that girl’s mother, that girl’s grandmother. She is the one to whom these images of perfection are being beamed.

Consider also Barbie’s opening use of the iconic 2001: A Space Odyssey musical cue (the one that plays when apes discover how to use bones as tools – specifically, tools of violence): children playing with banal dolls are shocked to see a gigantic Barbie, in the place of 2001’s monolith, towering over them, and, seeing this vision of femininity, destroy their homely baby dolls. The idea is that the discovery of femininity (through the Barbie product, of course) is a tremendous rite of passage that reinvents a girl as a woman, similarly to how the ability to use a bone for a non-bone purpose reinvents the ape as an early man. That’s quite a statement – that the acquisition of female body image is comparable to a monkey learning to hit; that, for better or worse, to be a girl in possession of a Barbie, and by extension of her own body, is to be transformed by that power. But of course, the blonde Barbie (Margot Robbie) in a swimsuit does not look like any little girl in a swimsuit, doesn’t even look like most grown women in a swimsuit. She is, apparently, the highest standard to which young women are to aspire (that this standard is governed by men is something only touched on in jest and brushed off as largely insignificant in the Barbie movie), a concept reflecting the corrupt culture of body image at hand in The Substance. So, when a horribly disfigured-beyond-recognition Elisabeth/Sue takes to the world’s stage in The Substance’s climax, and we hear upon her entering the spotlight that same 2001 musical cue, we can understand it to not only refer to a moment of evolution and revolution for E/S but also to a similar moment for the women and girls at home, in the audience, on the other side of the camera’s glow: the hideous, the contrast of Barbie, is finally being represented and given power. The destructive force, the tool of violence, is the very commodification of beauty; Barbie and Sue and (to a lesser but no less relevant extent) Elisabeth are cogs. What happens next is most telling, and the subject of our final homage.

Before we return to the events of that sequence, we must rewind to one of The Substance’s opening scenes. I can’t recall for sure if it’s the first time we see Quaid’s character, but it may as well be – it’s the first time we see his character. Elisabeth enters a stall in the men’s bathroom, and soon Quaid enters, unaware of her presence. The camera, with an extreme wide angle lens, is placed atop a urinal, which he approaches and uses rather aggressively (the splash of his piss, the frantic flopping of his penis below the frame, are constant reminders of the phallic which, if we assume the camera to constitute the eyes of the audience, is at our crotch-level) while just about screaming into his phone about his imminent decision to fire Elisabeth. The (of course) man on the line points out that Elisabeth has an Oscar – how will Quaid possibly wrangle another such genuine actor to do a hack fitness show – to which Quaid responds that her Oscar-talent and draw is long gone, with a retort something along the lines of, ‘What did she win for, King Kong?’. This reference stands out like a sore thumb: why King Kong, of all the old movies to choose from? Because the character she would have played (Fay Wray’s) was an actor herself, or was largely an inactive beauty in the hands of a monstrous ape? Because Wray didn’t, indeed, get the Oscar she deserved, or because she has, in conjunction with The Substance’s opening imagery, a neglected star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, that most surface award? No, the answer isn’t clear until the climax – that aforementioned sequence of the Elisabeth/Sue creature, now monstrous as Kong himself, reentering the camera’s glow. She pleads with the audience of executives and actors and models, all paragons of presentation themselves, that she is herself, Elisabeth, Sue, but her pleas fall on deaf ears. She is met with cries of, ‘Monster!’. And then, as Kong, she is senselessly attacked. I’m purposefully keeping this description away from the realm of spoilers – this is an experience not only wonderful but, in my opinion, deeply helpful, that I don’t want to sully for even the most reluctant possible viewer – but regardless of her end, the similarities are nigh endless, and the wraparound is fulfilled (yet another cliche subverted: that a woman such as the opening’s Elisabeth must represent a beautiful Fay Wray rather than the brute Kong, much the same way we expect her to be Barbie rather than Barbie’s opposite, or even Marion rather than Sara; in all cases, increasingly so in the order I have placed them within these parentheses, she is both).

Fargeat’s screenplay, in its first act, throws an incredible number of balls into the air, and quickly becomes a dangerous juggling act – as much as I was on the edge of my seat as to the events of the film, I was on the edge of my seat as to whether Fargeat would drop any of these balls (some of them eggs or perhaps flaming batons), and dammit, she never does. She catches them, in just a few scenes at the film’s end, all one atop the other, a towering shrine to the tragedy of the modern woman’s image. Yet the issue of the visual never compromises the visual artistry of the film itself; Fargeat presents her subjects with a paradoxical nightmarish naturalism, placing us in very real perspectives with pictures that often stray into expressionism. Our characters and their stories feel real even in liminal spaces, even as they interact with the fantastic, even as they are surrounded and infected by the body horror of a thousand stress dreams (the escalating prosthetics clearly do take inspiration from dreams, with exaggerations I’ve seen in my own but never before seen replicated – the effect is personal and bizarre, especially since we are often introduced to these prosthetics in first-person shots, looking in a mirror or down at a decaying hand). Fargeat maintains a steady pace of inventive imagery (and witty humor) throughout, in a way that would come off as a desperate gambit to aid a flailing story from a lesser writer/director, but here, thanks to that Cannes-award-winning screenplay and Fargeat’s unique yet cohesive ingenuity, add up to an undeniably purposeful whole. From the first frame her eye for symbolism is on display – my favorite example is of a fly swimming, then drowning, in the wealthy Elisabeth’s golden wine, killing itself in its gluttony (was it so thirsty for the wine, or was it simply drawn to the glow?). One most formidable symbolism endures: that of suicide by image.