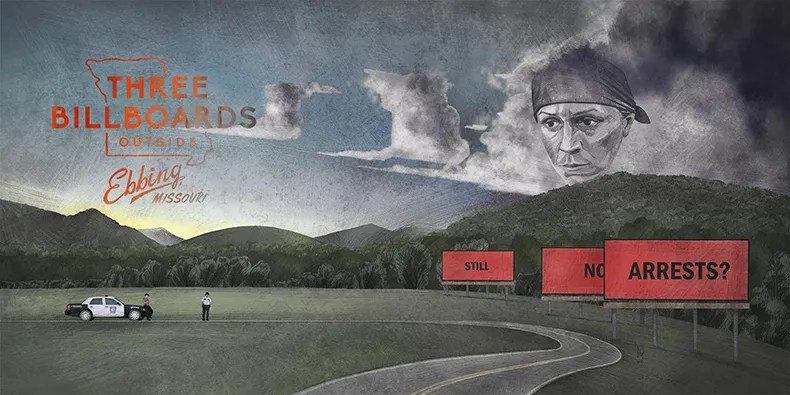

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is easily my favorite Martin McDonagh film. While many criticisms I’ve read from professional critics and casual moviegoers alike find fault in its perceived politics, I find these to miss the mark, as the writing is determinedly apolitical even in rubbing shoulders with hot-button issues. When, in the film’s emotional climax, Officer Dixon (Sam Rockwell) and grieving mother Mildred (Frances McDormand) begin to work together, their relationship was perceived by many as the culmination of a tale of redemption, and thusly criticized for absolving the characters. This is a misreading of the material, which takes care to show us that these are both dangerous people, Dixon physically and Mildred socially. Never does the film frame either of the two as having any sort of moral righteousness; Mildred is abusive and manipulative to her peers, while Dixon menaces the townsfolk with his fits of violence. In the final scene, the two are questioning the strength of their principles as they drive to Idaho to kill a man whose guilt they have no proof of. The movie isn’t framing Dixon or Mildred as redeemed, but rather as two extremely flawed people with no direction in life, seeking personal betterment through violence and hate, a course of action the story repeatedly defines as unhelpful and malicious.

The reap-what-you-sow, x-begets-x messaging quickly becomes excessive and moralistic, and as usual, McDonagh lets the thesis of his story get the better of it, but there’s nothing wrong with the oversimplified optimism of judgments such as, ‘you need love to be a good cop’ (until it devolves into ‘you need to love cops’). Morality plays, much like soap operas, are most effective when they put believable and realistic characters into almost unbelievable and unrealistic situations, and while McDonagh begins to stretch the audience’s suspension of disbelief, Three Billboards is verite compared to the heightened reality of his previous Seven Psychopaths or In Bruges – in part because of the ludicrous sociopolitical climate that makes all this so easily believable, but also because McDonagh is an adept storyteller.

Each character gets a meaningful final scene to end or cut short their arcs, except for the apparent protagonist, Mildred. Narratively, she functions similarly to ancient Greek gods in texts such as The Odyssey, interfering with the plights of mortals to test them, punish them or nudge them away from wrong and towards right. Her moralistic coldness, mirroring the warm moralism of the film, pushes all those close to her away, from her son Robbie (Lucas Hedges) to her transactional dinner date James (Peter Dinklage), while her drive for justice keeps her ignorant of the hurt she is causing. She is an instrument of fate, a common motif in McDonagh’s filmography – his stories rarely end complete, but the endings are always meticulously built up to, each scene existing to lead to that final event (or lack thereof).

Fate has no place, however, in the aftermath of Chief Willoughby’s (Woody Harrelson) suicide. The letters he had written to various important townspeople are read at pivotal moments throughout the plot, informing the relevant character’s emotions and subsequent actions. Willoughby evolves into a guardian angel, becoming involved past his death only when a dire situation calls for no other solution. Perhaps the true redemption here is his: after years of complicity, letting a rapist and murderer go free, allowing Dixon to abuse his power, he is finally able to help the people of Ebbing, Missouri. Or, in the end, did he only send two unstable criminals on another road to anger that begets anger?

I guess we can decide along the way.

Mildred Hayes