The Giallo film genre is one that’s quite difficult to describe. It defies labels and traditional classification, meshing thriller and mystery and horror and slasher and exploitation and eroticism to create a wholly unique whodunnit experience, one where the ‘who’ is sidelined in favor of ‘what’ and ‘how.’ But that’s not a great elevator pitch, so when I recommend the genre to friends I typically describe Gialli as violent Italian murder mysteries. I’ll admit, it’s a blatantly inaccurate definition; a Giallo is not a murder mystery, but rather a murder film in which the protagonists aim to solve a mystery. That mystery is never posed to the audience, except when it comes to experimentalist horror filmmaker Lucio Fulci.

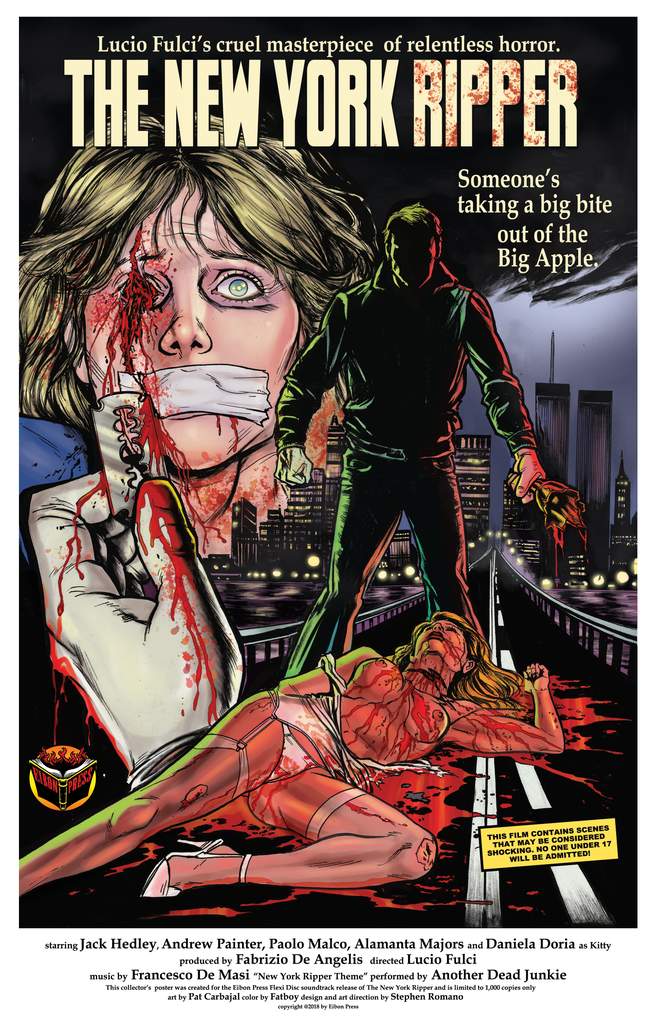

Fulci is known for his fantastical, sexual movies, with bombastic camerawork and fast-paced editing. He would often state that as a horror director, he felt jarring visuals and audio to be necessary for building suspense, an assertion that he wielded against more subtle horror films such as The Shining. “I couldn’t care less about this guy who goes mad in The Shining. I hate The Shining anyway; Kubrick’s coldness was alright for A Clockwork Orange or The Paths to Glory, because it corresponded to the story. But Kubrick’s genius is not made for horror films. The Shining has no feeling.” (cultcollectibles.com) It was this conviction that led to his creation of perhaps the most influential Giallo ever made: The New York Ripper.

The New York Ripper, or The Ripper, as Fulci often called it, opens with a man playing fetch with his dog. He throws the ball into a bush, and the dog returns from the bush with a severed arm. This discovery leads to a local detective attempting to track down the killer, dubbed The Ripper. What follows is a series of brilliant manipulations of the audience from Fulci. First, the supposed killer is revealed a third of the way through the movie. In creating this plot development, Fulci expertly toys with his viewers’ knowledge of a typical story; it’s obvious that the narrative tension would fall flat if the killer was outed so quickly, therefore this man cannot be the true killer. So, the question turns from ‘who is the killer?’ to ‘why is he not the killer?’ Once the man dies a few scenes later, the question reverts to its original whodunnit state.

This altering of the viewing experience is something quite jarring, and intentionally so. When the film repeatedly subverts itself throughout its runtime, it becomes untrustworthy and dangerous. Not only do we become afraid of the events the film depicts, but of the film itself.

The falsely confirmed killer is only the beginning. In fact, it effectively serves as a preparation of the audience for the rest of the movie. After the perceived killer’s death, a number of suspects are all but confirmed as the killer, and then proved not the killer, in quick succession. This narrative structure solves the quintessential issue with whodunnits: what is advertised as deduction on the part of the audience is in truth a guessing game. Sure, there are sometimes clues sprinkled throughout the story, making it somewhat possible to figure out the evildoer, but these so-called clues are so contextually enigmatic that one can only notice them after experiencing the reveal. Fulci does away with this problem by making the question not one of clues, but of character. As the film makes every character a suspect, and eliminates them one by one, it forces each audience member’s theory to evolve over time rather than remain stagnant and be either confirmed or denied by the climax. What is typically a static, unstimulating viewing experience becomes exciting and unique, a truly thrilling narrative mystery to match the literally thrilling events unfolding on screen.

By removing the dissonance between the plot structure and the individual scenes, Fulci injects his film with incredible emotion. It is here that his criticism of The Shining is made relevant to his filmic technique; The Shining, a mystery of its own rite, is purposefully cold to mimic the ghostly power of The Overlook Hotel. This coldness, however, is at odds with The Shining’s scares. A man being killed with an axe, blood pouring out of an elevator, and a man giving oral sex to another man in a bear suit are not cold events. If they were, they wouldn’t be frightening. But perhaps, as Fulci posits, they would be more frightening if their narrative and physical atmosphere matched their excitement.